KMD Architecture and the Neoliberal Aesthetic is an ambient institutional critique that combines scenographic elements with a spatialized academic process. It focuses on the University of Bergen faculty of Art Music and Design’s (Kunst Musikk Design, KMD) new building in connection to the additional policies and adjustments to the education that came with it. The research examined the type of subject that is conditioned and the type of work that is possible within the conceptual bureaucratic structure of the university and the physical architectural structure of the new building.

The work approached aesthetics as functional, not just in promoting an ideology, but in creating environments that passively condition the subject — in this case, the “student-entrepreneur”. Viewing neoliberalism as the hegemonic order, the spatial features are brought forward through research images, and connect to an academic thesis of excerpts within book scans.

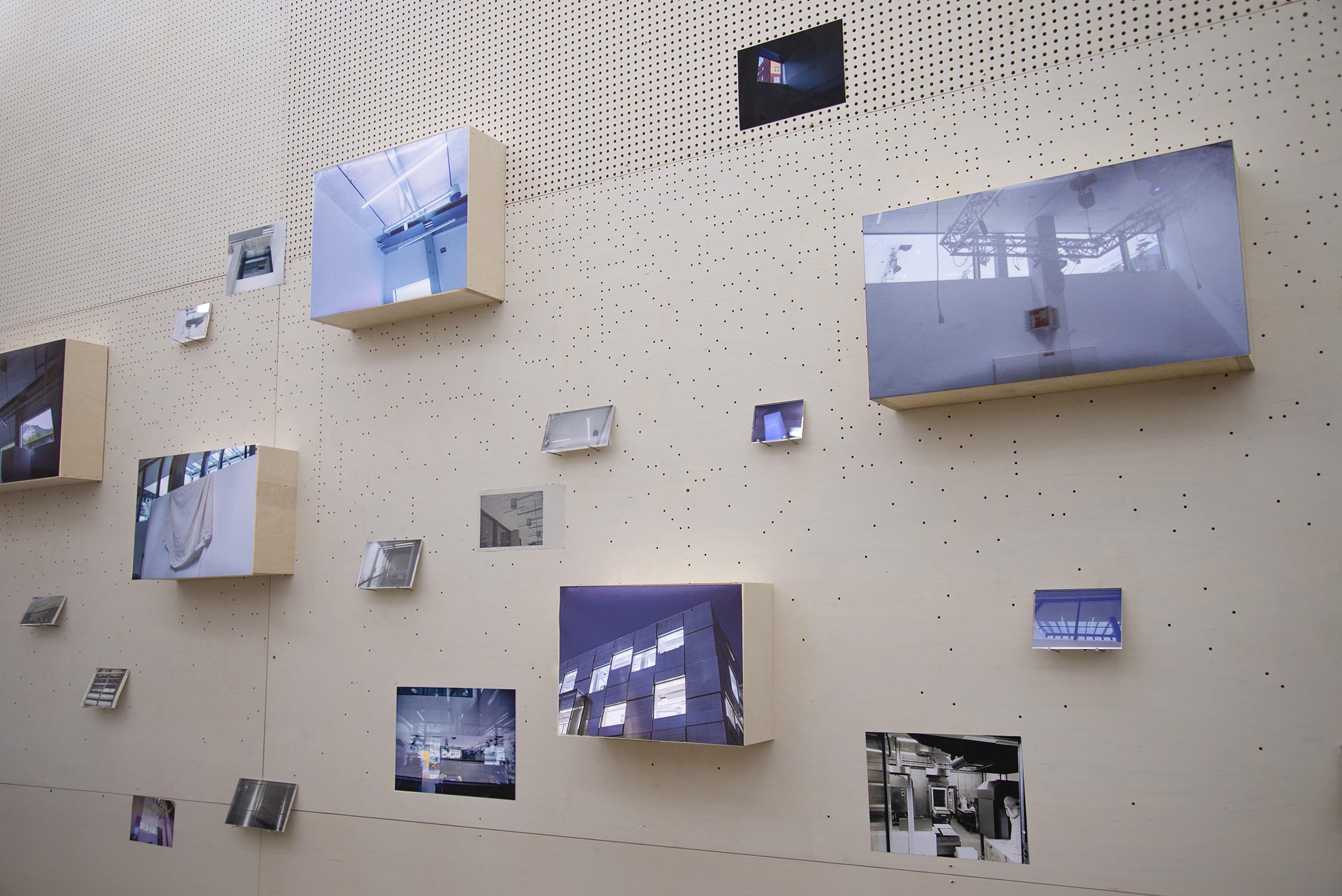

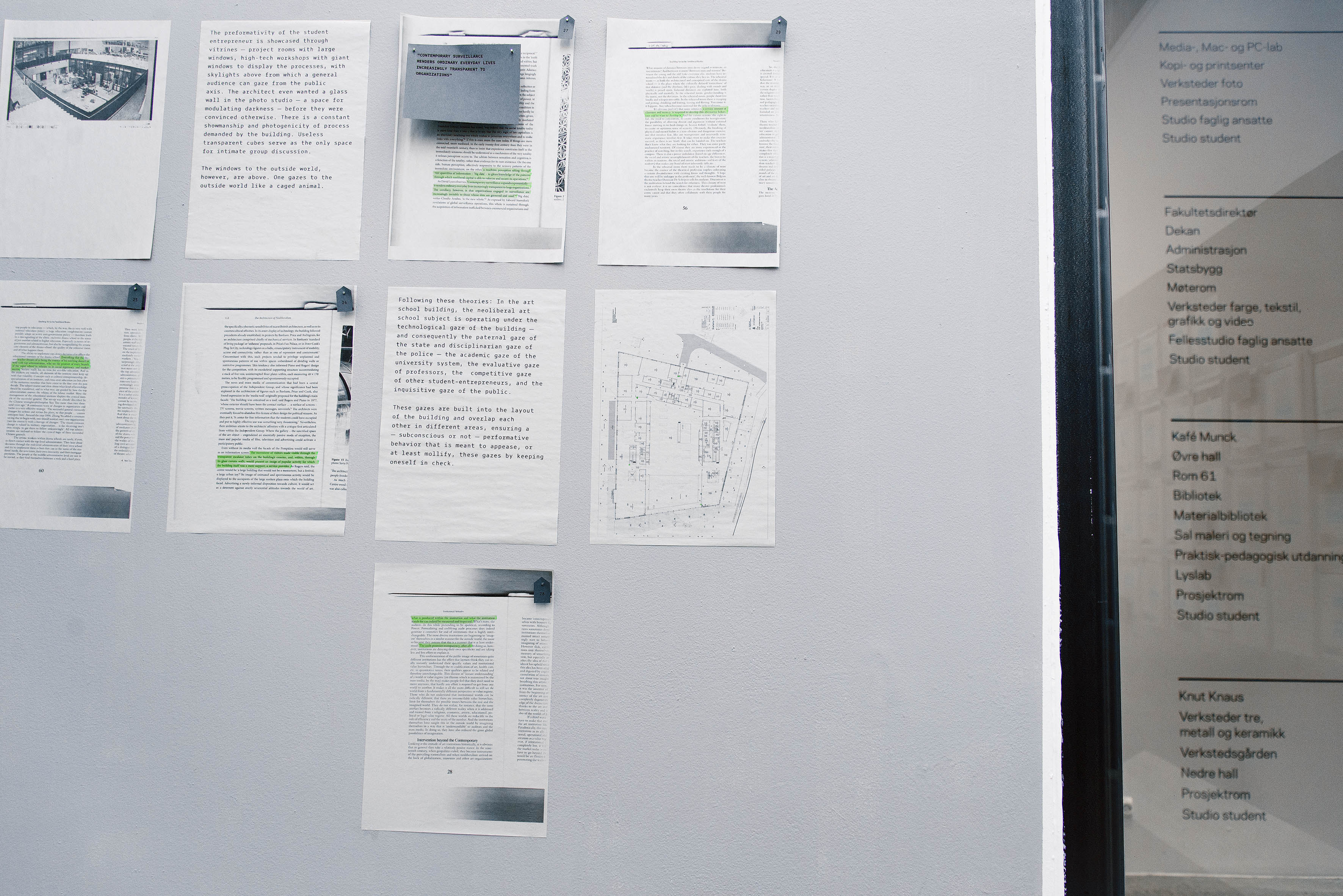

The building was examined as a hybrid of an art gallery and university (“a space for showcasing the process of creating artistic work”). Special focus was placed on the unusual window structures of the building that created areas of overlapping gazes and turned the process of creating work into a performative behavior; on the concept of the “smart building” which outsources the agency of the individual and requires self-disclosure for adjustments of space, and on the prioritization of technological and bureaucratic efficiency over human agency.

The building was examined as a hybrid of an art gallery and university (“a space for showcasing the process of creating artistic work”). Special focus was placed on the unusual window structures of the building that created areas of overlapping gazes and turned the process of creating work into a performative behavior; on the concept of the “smart building” which outsources the agency of the individual and requires self-disclosure for adjustments of space, and on the prioritization of technological and bureaucratic efficiency over human agency.

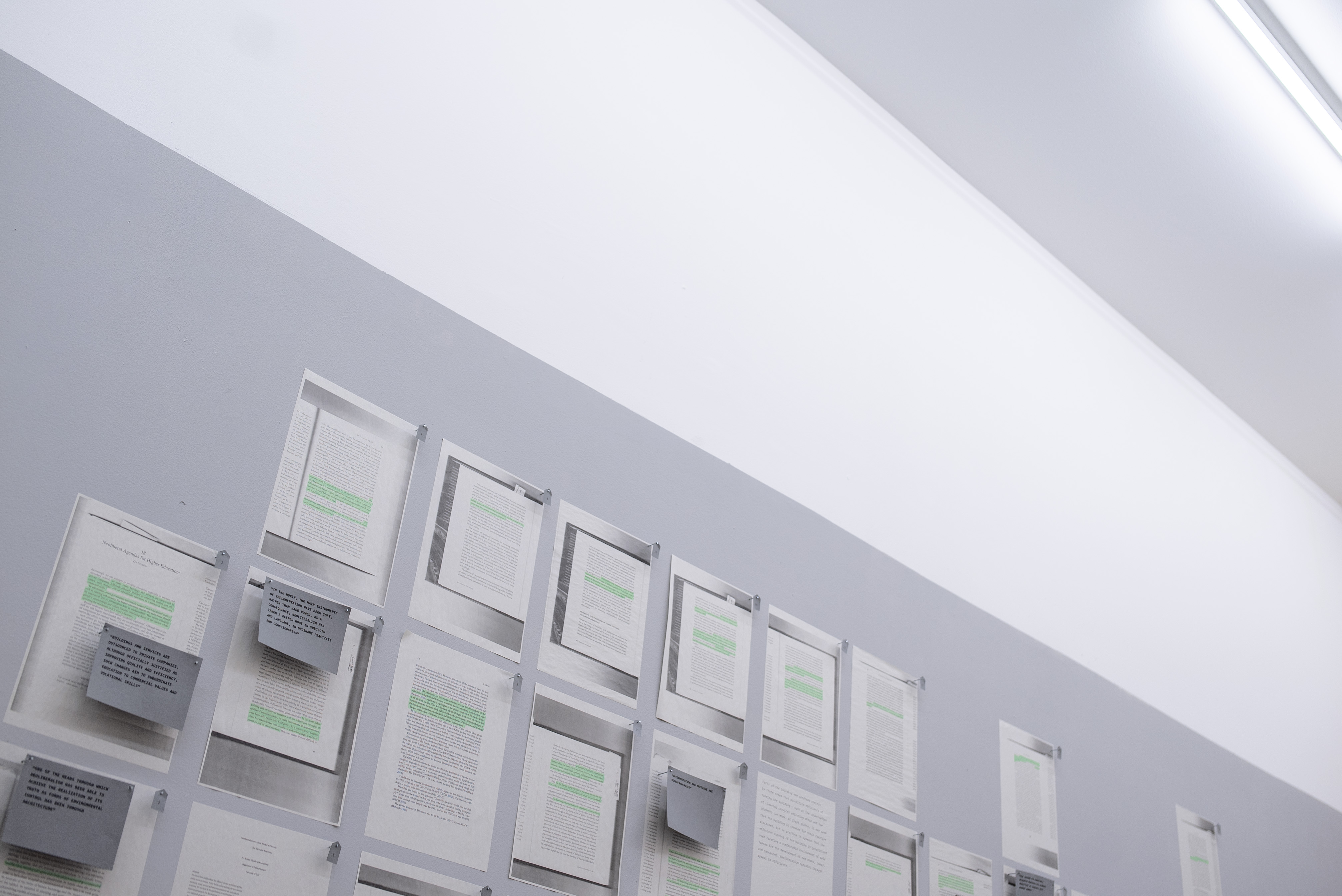

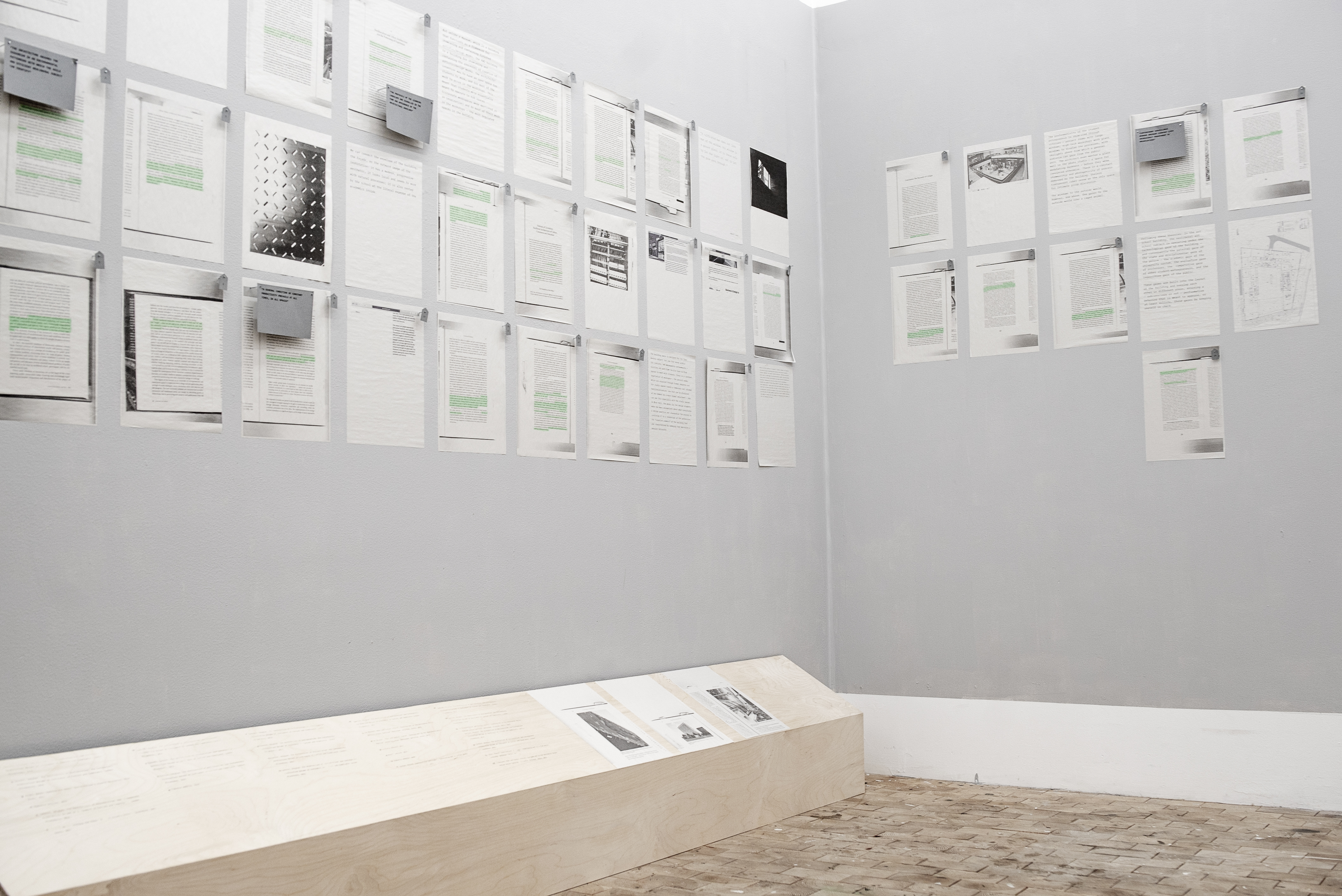

The installation assembled photographs and ambient videos of the building to develop a scenography from certain aesthetic qualities of the space, and then interrogates the hegemonic undercurrents through a collage of excerpts from different books on neoliberalization of education, architecture, and the art/design institution.

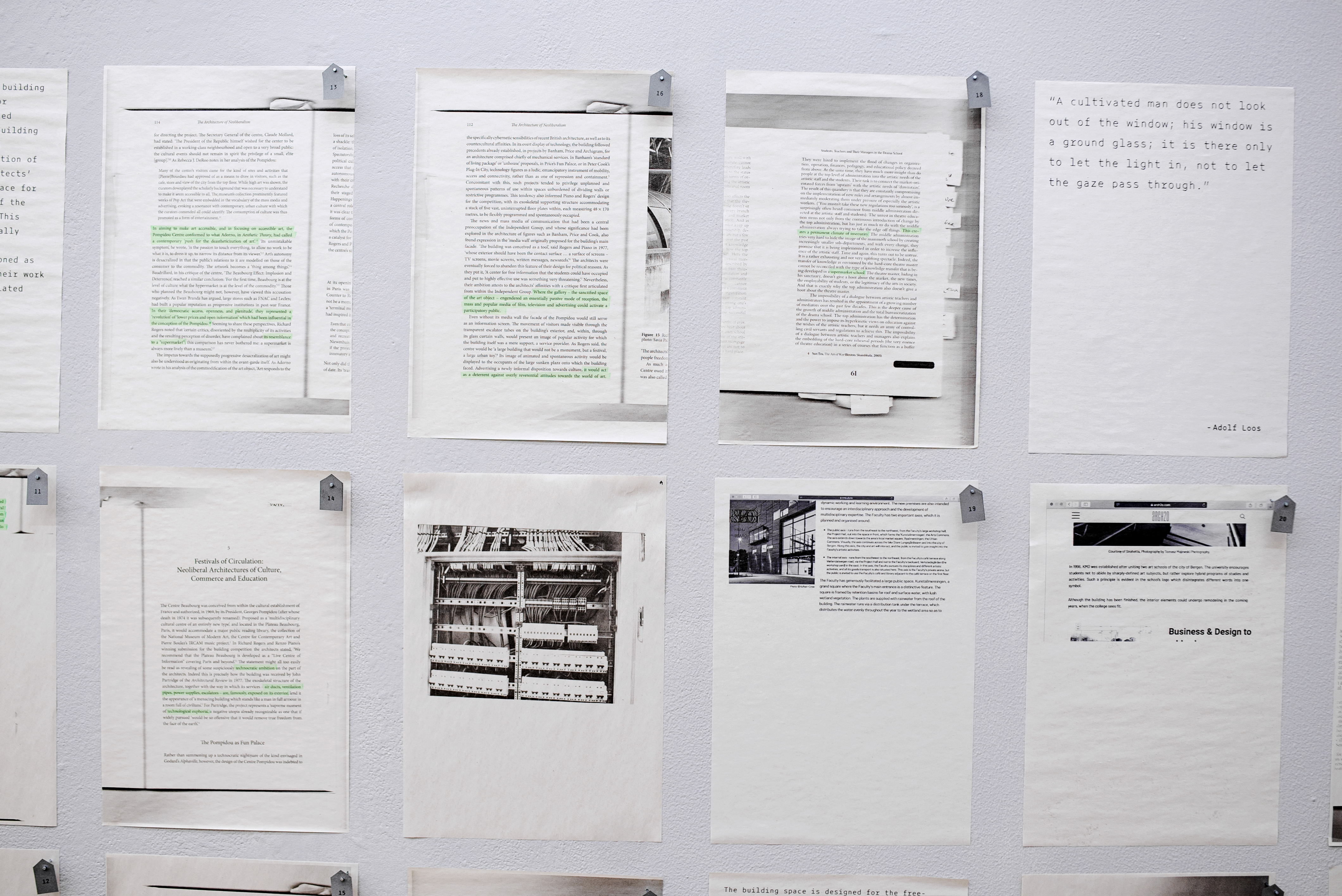

Using the performativity of the humanities process, the text portion of the work assembled the texts into constellations that played off of each other and constructed a thesis. Portions of the thesis written by the artist based on research observations in connection to the texts receive the same treatment as the book scans, taking on a similar authority as the published texts. As part of the fetishization of the academic process, footnotes were printed on wooden boards at the foot of the walls of text, connecting to numbered tags on each page.

Using the performativity of the humanities process, the text portion of the work assembled the texts into constellations that played off of each other and constructed a thesis. Portions of the thesis written by the artist based on research observations in connection to the texts receive the same treatment as the book scans, taking on a similar authority as the published texts. As part of the fetishization of the academic process, footnotes were printed on wooden boards at the foot of the walls of text, connecting to numbered tags on each page.

The highlighted excerpts are presented as part of the original texts and are arranged in a fragmentary way, where meaning is created through their relative positioning and the different books validate each other as well as the written passages about the university building. There is no narrative, however: they form an ambient spatial critique that can be entered from any area and still understood; The work is arranged for contemplation and immersion in the texts.

view promotional material from exhibition

artistic/academic citation for project:

Gouzikovski, Victoria. KMD Architecture and the Neoliberal Aesthetic. Ambient Institutional Critique. Joy Forum. Bergen, Norway. 2019.

view promotional material from exhibition

artistic/academic citation for project:

Gouzikovski, Victoria. KMD Architecture and the Neoliberal Aesthetic. Ambient Institutional Critique. Joy Forum. Bergen, Norway. 2019.

Thesis texts (raw text from exhibition): “The smart building prevents the subject from being active in the building. One cannot simply open a door, one must request for it to open by signalling to a motion sensor; The temperature in most rooms is adjusted by the government agency, if a lightbulb breaks one needs to call in an outside company, you must prove your legitimacy before entering workspaces with a code. When all of these things like opening doors, turning on equipment, changing the temperature (is outsourced to multiple agencies and administrators) require permission, this leads to every mundane activity to be regulated; Why do you need the lights on in that room? What will you be doing in there? Why can’t you do it elsewhere? Who gave you permission for this?””

raw thesis texts (integrated art writing): “By turning academic matters into administrative matters. True criticism, questioning, or production of new knowledge (which by definition does not play by the rules of the current system of legitimation) are not recognized in this system unless they keep up neoliberal appearances. In this context, power structures are only highlighted in favor of those in power, such as when implementing rules, but almost never mentioned to acknowledge the inherent power imbalances within these interactions.”

“So while people may not always see overt disciplinary functions, especially if they play by the rules of the institution and don’t question anything too actively, you can see these subtle creeps of disciplinary currents into the institution through surreptitious processes under seemingly innocent and logical reasons like installing the surveillance cameras on the second floor (for “safety”), keeping students out of the third floor (“to protect documents”), keeping open-plan offices for design students (“so they are easier to find”), While these processes may indeed serve those functions, it formulates the question about what type of dynamic this is creating as a whole: Students are meant to be radically transparent while administration is actively opaque, the building is made so that the subjects of the building can be viewed at any time, but are those watching them trustworthy themselves?”

“Any topic can be discussed, but only within the formats: the framework of the lecture, the framework of the classroom, the framework of the institution, the framework of the discipline. “Transgressive” subject matter is allowed, but anything that disobeys the format is delegitimated, excluded, or punished. Alternative thought processes are viewed as tangents or disruptions. One can only criticize the system in safe and socially acceptible ways -- modes that render the critique non-treatening and even useful for the dominant order. In the building, this manifests as going against efficiency. Creative practices are sidelined in favor of a well-maintained building. The building keeps everyone in their place, but also mobile within its modes of operation. Maintaining the framework in the name of formalities keeps artistic processes in the defanged realm of suggestion, and turns designers into window dressers for neoliberalism.”

“Under the gaze of these formal systems, interactions become transactional and academic decisions are made in a businesslike, economic fashion. The humanism is hollowed out through bureaucratic mediation.”

“The academic institution is meant to be a liminal space for the creation of knowledge, for reimaging the world in new ways, and for developing new processes. For art and design students it is meant to be a suspension of time where one can work on new ideas outside of the dominant economic system. When one of the few remaining spaces for this kind of work becomes placed under regulations, surveillance, and organization in the name of obtaining legitimacy from the hegemonic order, the institution becomes a place for processing students into neoliberal subjects through a modular system that aims towards checking off requirements as exercises in obedience.”

This research project examines the new building of Fakultet for kunst, musikk og design (KMD) after the merger of the University of Bergen and Kunst- og designhøgskolen i Bergen (KhiB) at the location of Møllendalsveien 61, 5009 Bergen

Excerpts from semi- academic text about the research: (these are images from the thesis, raw text below)

(pages 59-70)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Project Bibliography, page 107 of thesis text:

academic citation for this portion of thesis text (below):

Gouzikovski, Victoria. Alternative Stabilities. University of Bergen, Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design. Bergen, Norway. 2020.

Gouzikovski, Victoria. Alternative Stabilities. University of Bergen, Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design. Bergen, Norway. 2020.

(pages 59-70)

Project Bibliography, page 107 of thesis text:

Raw Text:

(from: Alternative Stabilities, Mater Thesis 2020)

KMD ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEOLIBERAL AESTHETIC (concepts developed)

The Appeal to Efficiency

The most immediate concept derived from the research is the appeal to efficiency and the prioritization of technology over the individual. The idea that technology and the optimal functioning of the system (in this case, neoliberalism) is more important than respect for the individual, individual agency, interpersonal relationships. When humanistic education is (mis-)placed into a neoliberal structure — both of bureaucracy and architecture, it becomes destroyed because the core element of those studies rely on mutual trust and respect, concepts that are entirely irrelevant to the dominant system of ordering.

The concept of efficiency and pure functionality is seen as the ultimate goodness in the neoliberal ideology, so the building celebrates its sterile qualities. Because of this, it is not just that the building does not offer comfort, or even that it does not make room for comfort; but that comfort itself is not allowed; being seen as both a safety issue and an impediment to the efficient running of the building — simultaneously enforcing the idea that its inhabitants must be constantly active and productive.1

The “Smart Building” as an Outsourcing of Autonomy

The automation of the “smart building” outsources autonomy to building and the state. The designer of the building makes multiple assumptions about how people in this institutions should behave, and then creates ways that leave little room for individual uses — the doors open only through motion sensors (that don’t even work smoothly), the lights turn on for the user, and yet if anything needs adjustment one must turn to the state, which requires self-disclosure (“why are you using that room?” “do you have permission?” “what do you plan to do in there?”) For example, changing the temperature in a project room requires a request to be made to the company that owns the building, lightbulbs take a few professionals to change, and access to different rooms must be granted. Automated environments passively implement obedience. It is like the ultimate psychological manipulation where one is controlled under the guise of being assisted. “Let me make this easier for you” the building says, making assumptions and creating virtualities about your behavior.

The Theory of the Multiple Gazes

The theory of the multiple gazes was more fully developed in this project. The window structures within the building create vast fields of visibility; for instance, Øvre hall, designed to be the “creative commons” of the building, is a field that can be viewed by the authoritative gave of the state and the punitive gaze of the police (through the technological gaze of the security cameras), the disciplinary gaze of administration, the evaluative gaze of professors, the — in this context — competitive gaze of one’s peers, and the inquisitive gaze of the general public. The project rooms often have the overlap of fewer gazes: professors, other students, the wayward visitor, yet they are also vitrines for showcasing processes. The open-plan working quarters permit a bit more privacy yet are always open to spontaneous visits from students and faculty. All of these have different types of panopticism but if one takes, for example, the project rooms with large glass windows: they are a space that puts the processes of art and design on display and generates a sort of performativity to the actions. This then enhances disciplinary functioning in many senses: self-regulation in front of others, obedience to the rules, and the articulation of formalizing movements of the disciplines (for instance, a painter would be pushed to act more like a painter, wielding a brush and stepping back to look at the work occasionally, a designer more likely to mimic the actions of a designer in a studio, using sticky notes on walls, drawing large mind maps, and sitting at a laptop, a video artist would take on the actions of a cinematographer, etc.)

The Window Structures of the Building

The concept of transparency2 is articulated both through the bureaucratic attitude (it is not enough to be honest, the student must be forthcoming, anything less is lying. The student must be self-disclosing to administration and faculty, yet most of the functioning is entirely opaque) and the structures of the building: students are constantly seen, professors often have temporary refuge in (sometimes shared) offices and yet the third floor is entirely opaque and unaccessible to students. In terms of visibility, the student is always open and exposed, (personal constructions for privacy are seen as a safety hazard) flexible, and available. While at the same time, an unweildly bureaucracy finds it too difficult to adjust to newly emerging creative practices, choosing instead to make administrative decisions in academic situations.

The Hub Space

Nomadism is often seen as a way of evading the hegemonic order, but with the introduction of the hub space in neoliberal architecture, the concept of nomadism becomes integrated into neoliberal strategies. It offers small sections of “smooth” spaces for individuals to navigate, at the same time refusing to provide any symbolism that the subject could critically analyze, giving away cognitive agency to their environment. At the end of The Smooth and the Striated, Deleuze warns: “Never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us” (Additionally, in Nomadology and the War Machine, it is described how nomadic tactics are often used by the dominant forces as well.)

The Commons as Synthetic Equalizer

This leads to the idea that the commons created a field of synthetic equality, that can harness the energies of subjects that are not treated equality within the system — as neoliberalism runs on the dynamic of inequality — to use towards the progress of the very system that subjugates them3. That by creating architectural spaces of the neoliberal version of openness, transparency, and freedom, the energies that are generated in those spaces become productive towards neoliberalism.

1 ALSO PRESENT IN FOUCAULT, MICHEL, DISCIPLINE AND PUNISH: “THE DISCIPLINE OF THE WORK-SHOP, WHILE REMAINING A WAY OF ENFORCING RESPECT FOR THE REGULATIONS AND AUTHORITIES, OF PREVENTING THEFTS OR LOSSES, TENDS TO INCREASE APTITUDES, SPEEDS, OUTPUT AND THEREFORE PROFITS; IT STILL EXERTS A MORAL INFLUENCE OVER BEHAVIOUR, BUT MORE AND MORE IT TREATS ACTIONS IN TERMS OF THEIR RESULTS, INTRODUCES BODIES INTO A MACHINERY, FORCES INTO AN ECONOMY”P210

2 FOUCAULT, MICHEL. THE BIRTH OF BIOPOLITICS, LECTURES AT THE COLLÈGE DE FRANCE 1978-79. ED. MICHEL SELLERT. TRANS. GRAHAM BURCHELL. NEW YORK. PICADOR, 2004.

3 “BENTHAM’S PROJECT AROUSED SUCH GREAT INTEREST BECAUSE IT PROVIDED THE FORMULA, APPLICABLE IN A WIDE VARIETY OF DOMAINS, FOR A FORM OF “TRANSPARENCY”, A SUBJUGATION THROUGH A PROCESS OF “ILLUMINATION” FOUCAULT, MICHEL, “THE EYE OF POWER”

4 THIS CAN CONNECT TO A CONCEPT IN MOTEN AND HARNEY’S THE UNDERCOMMONS; THE IDEA THAT BY PRESENTING ONESELF AS A SUBJECT IN SOCIAL OR POLITICAL PARTICIPATION, ONE SUBJECTIFIES ONESELF WITHIN THE SYSTEM.

KMD ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEOLIBERAL AESTHETIC (academic research)

The thesis for the academic portion of the research uses Foucault’s definition of neoliberalism: as the constitution of the neoliberal subject through market logic. The way that it manifests as a mentality in Norway: through the application of the market mentality to the public sector, rather than overt privatization. And how it is then diffused as a mentality through its manifestation as “common knowledge” (through hewing to social norms and the redefinition of terms) and through the design of architecture. This definition includes the idea that Neoliberalism is a form of governmentality - a rationality of governance that conditions the conduct of subjects in a particular way, a series of political and economic processes that direct everything towards the support of the free market, an ideology presented as matter-of-fact.

Aside from promoting a free competition among markets, neoliberalism promises a freedom for its subjects. But the type of freedom that it promotes is mostly a freedom within itself: Neoliberalism wants “free”, mobile, flexible subjects that move within its circuits. Unlike nomadic movements, neoliberalism wants free-moving subjects that can be carried by it rather by their own free will, and it ensures that they do by presenting itself as common knowledge and producing self-regulating subjects that have internalized its rationality.

In Foucault’s Birth of Biopolitics1, he describes neoliberalism as requiring inequalities to operate. So it needs to continuously create and exacerbate inequalities in order to thrive. It creates need and then offers solutions for it. (It is important to note, that at the time of these lectures, neoliberalism was not hegemonic, so his analysis was only highlighting the emergent currents of the ideology.)

In this way, neoliberalism mobilizes everything to operate within its systems: standardizing everything to make sure that it can be used as data, that it can be measured by the metrics of neoliberalism, and that a utility is derived from every resource; and within neoliberalism, everything becomes a resource: even the spiritual. These resources then rely on inequalities that fuel neoliberal processes. Everything is made to be productive towards the progress of neoliberalism, and any sort of reforms are then talked about within its confines (including “progressive” reforms like the circular economy).

Since the subject also internalizes neoliberalism, they begin to view themselves as an enterprising individual, basing their value on neoliberal metrics, and placing their self-worth on their utility and productivity within the neoliberal hegemony. Their behavior is based on capitalizing on opportunities and marketing themselves, while making themselves more observable and measurable within the system.

In education, this means that the student is viewed (and conducts oneself) as a student-entrepreneur. One that is at school to acquire marketable skills and a portfolio of competencies so that they can better position themselves in the market. This is also combined with neoliberalism’s need to turn everything into data and to measure everything. For this there are ways of measuring the students capabilities within the system, not just “translating” everything into quantifiable activity — measured on how useful it is to the system — but also imposing a framework of measurable activities onto them. In this way, students are conditioned into neoliberal subjects and to cope with this, students — and society, in general — are offered therapy and self-help advice on how to continue to be useful subjects to neoliberalism and become the best entrepreneurs to the system. It allows them to raise their self-worth by raising their productivity and desirability to the system. Everything within this system needs to be measurable, so time, energy, and activities are organized into modules that are then used as frameworks to condition the subject. Neoliberalism operates on a large scale, so bureaucracy is designed for a large scale and administration is downsized — making fewer points of interpretation — and students become treated as data in the name of fairness. Fairness in neoliberalism, in order to be efficient, is non-qualitative, and views all subjects based on a few selected metrics — metrics that are useful to the system. It then uses these metrics to asses which students would be most useful to it, which ones would be more efficient and effective to process into the market, and which ones are most reverent to its rationality. In art and design education, this means attempting to — at best, try to find a way to quantify these practices — and at worst, trying to create quantifiable modes of practices for this field. So not just translating these practices into some sort of “rational” metrics, but actually changing the academic processes to generate quantifiable activities.

This research examines how this is implemented through a combination of bureaucratic processes that implement these activities, and the framework of the building, which conditions conduct through the same rationality.

Neoliberalism operates through appeal to efficiency. In academics, bureaucracy and the flattening of subjects into data create efficiency. Anything that goes against this order, is seen as going against progress. Following Foucault’s comments on neoliberalism, bureaucracy creates problems and then offers solutions — there is a sort of disorienting atmosphere that is created by unnecessary formalities, and then more rigid formalities are placed on the subject to “solve” the chaos.

In architecture it is implemented in many ways: through the efficient running of the building — the KMD building only needs people to activate it and maintain it. Many activities are curtailed in favor of keeping up the efficiency and safety of the building.

The entire building seems to be designed around anxiety emergencies: hallways must be cleared, there are glow-in-the-dark markers and signs with running stick figures along with escape arrows all over the building, soft furniture is not allowed in the studio spaces as a fire hazard, everything is locked with key card access.

Neoliberalism in the Norwegian context is very in line with the Foucauldian notion of neoliberalism. Here, the rationality is dispensed by the state. A critical reader on Neoliberalism2 discussed how welfare states tend to rely on social solidarity, which already means that migrants and people on the margins are excluded. This also means that the main way that this type of society shifts into neoliberalization is through the redefinition of terms. It would be difficult to change society’s traditions to other systems, but it is very effective to begin changing the meaning of certain themes by assimilating them into the market mentality that is already presented as common sense; this way, “freedom”, “security”, “fairness”, “transparency”, “equality”, “democracy”, take on entirely different meanings and catalyze subterranean cultural shifts towards neoliberalism. These shifts are often much more deeply rooted because they take place within the collective mentality and cannot be overtly identified.

This bureaucratic/academic structure connects to the structure of the building. The work examines two case studies from the book Architecture of Neoliberalism3: One that looks at Ravensbourne College, and one that examines the Pompidou Centre as neoliberal structures, and comparing them to the KMD building. It examined the idea of the hub space, a place that allows freedom and “nomadic” behavior, where people opportunistically find spaces to talk and negotiate spaces to operate in — also a place where anyone can be viewed at any time. It is the hallmark of the “progressive” corporate space: a space that says “this is a fun place to relax and work” — and here, there is no distinction between work and free time: breaks never really feel like breaks and the thought of work is constantly present during times of leisure. “A general feeling of constant productivity prevails at all times”, writes Douglas Spencer — in neoliberalism, even leisure is made productive. Google workspaces were mentioned as an inspiration for the KMD building, and so there are hub spaces that create this type of atmosphere throughout the building. Another characteristic of neoliberal architecture is visibility: both Ravensbourne College and KMD have a public and private axis, with the public axis creating a field of visibility for the public.

These theories are then connected in the examination of the window structures within the university. The windows to the outside world are above, to make room for “museum walls” but also utilizing windows as light sources, not as something that one gazes through. The interior windows, however, become vitrines for showcasing the artistic processes. This then enforces a performative aspect to the creative processes occurring in the building: everything is for everyone, everyone is transparent, there is nothing that is not done for someone else’s gaze. There are windows in the floors and ceilings, windows into every room, and large panels of glass as walls.

This is then developed into a theory of multiple gazes: In the building, the student operates under the gaze of the state and police (who are connected to the surveillance cameras on the second floor), the evaluative gaze of professors, and — in the context of the “student-entrepreneur” — the competitive gaze of other students. And with the concept of the private axis, in theory, they are also under the public gaze; Not just in the public axis of the building, but also in terms of the requirements that they have checked off and the data that their activities generate that then goes under the scrutiny of detached entities.

What does this make of the “creative commons” of the buildings? Connecting the second floor space designed to be the “commons” at the KMD building to the previous research on Torgallmenningen, the concept that is supposed to be the progressive solution towards multiplicities and equality is examined. How can we feign “equality” within a series of unequal power structures? When people’s subject-positions require different energies to make contributions to the commons, and then others have more prominent voices and more accessibility to legitimacy, when peoples’ capabilities have different values and impact, how can we pretend that the commons are a great equalizer? And when placed under multiple gazes and processed into the neoliberal mentality, the commons become an open space that not only removes any possibility of architectural critique, but also becomes a space where the subject relinquishes any self-direction or resistance to the free space of neoliberalism. This leaves the subject to territorialize the space in a neoliberal way — for instance, some design courses in Øvre Hall become a series of forced, quantifiable activities done in a neoliberal style under the guise of a progressive freedom and “creativity”, at times under the gaze of professors imbued with the idealism of the neoliberal rationality, uncritically producing objects that fit into the dominant social order — only different in style because that is all that can be retained within these frameworks — alternative ideologies become hollowed out through the formalities of the neoliberal framework and only what is useful to it is preserved and offered protection. Without addressing the dominant rationality, the commons become a way of sublimating any counterculture or alternative creations into more fuel for neoliberalism and more content for the people on top of the hierarchy. In this way, the commons is treated as an equalizing safe space for voices to be heard, but really only creates the illusion of a safe space that encourages people to open up and become vulnerable so that their energies can be exploited. A passive field for the blossoms of critique to bloom so that they can be harvested and distilled by neoliberalism.

What is meant to be a liminal space for developing new practices and solutions for the world, a safe space that protects individuals as they push themselves psychologically, mentally, emotionally, and even physically becomes an energy-harvesting device when the mentality of the hegemony is applied.

Instead of providing small spaces of time, physical space, and mental space where students can be vulnerable so that they can push their work for a brief second, be elevated/suspended into a theoretical realm, away from the dangers of this type of exploration in the corporeal world, the institution that asks students to be open and vulnerable without providing any protection from the violence of bureaucracy and neoliberalism then becomes a mechanism that renders the students docile and malleable for the social realm, it objectifies, subjectifies, and prepares the body, mind, and soul of the student for integration into the hegemonic order by making their energies productive for it.

Terms that are seemingly friendly become redefined: “Fairness”, for example: rather than being qualitative everything is the same, there is no discernment. This maintains hierarchical power structures while at the same time keeping people within disciplinary confines. This is not an equality that is based on respect for others, it is a redefinition that has punitive effects on anything that disobeys the framework — a positive way of keeping people in their place.

This “redefinition of terms” concept is also tied to the idea of appropriation, absorption, and co-optation of any counter-practice by neoliberalism. Apple computers made appearances in both the architecture book4 and the teaching art book5 . The architecture book talked about how Apple computers arose out of the counterculture of freedom, of the open road, and turned this freedom into a totalizing enterprise. The teaching art book discussed how standardization in education was aided by the adoption of Apple computers as the main operating system used in creative practices (especially design). The architecture book also uses the appropriation of the theories of Deleuze and Guattari and of Affect Theory by neoliberal architects to implement a neoliberal conception of freedom. These theories are used as conceptions of freedom that omit any possibility from critical thought; they are used to support the idea of open, parametric landscapes free of any type of symbolism that “unburden” the mind from any discussion or evaluation of the architecture and give themselves over to the flows of neoliberalism. In this way, hub spaces, open floorplans, repeating patterns, all create a space where the subject gives oneself entirely to the circuits of their environment.

In my analysis of the KMD building, I also examine the theme of the “smart building” as a space that gives a feeling that the little things are taken care of (things that are considered givens based on assumptions) and yet that one is completely overpowered by technology. In this case, it is as if technology is a higher power. At KMD, the doors open without your physical effort, but you need to ask permission from a motion sensor, the lights turn on for you but if they malfunction one is helpless without a technician, the temperature can be adjusted only with the help of the government organization that owns the building. The entire machine shuts down at midnight and you can only get out. Students are tracked every time they use their key card to access a room. This creates a sort of helplessness, a reliance on the higher power of neoliberal technology.

A complete domination of the technologies of the building that sociopathically makes assumptions about your needs, makes you completely dependent on it, and then makes you seem like a criminal if you color outside the lines with your routine. The public axis of the second floor have cameras that are maintained by the state.

So the subject of the building and bureaucratic structures needs to be always open, forthcoming, visible, transparent, flexible, empathetic; while the administrative quarters are opaque, the mechanisms of operation of the building are obscured and out of reach, the bureaucracy is rigid (for efficiency) and policies are unfeeling (for fairness). A severe imbalance of power is upheld through these structures that leave no room for non-quantifiable practices.

The entire building and system is constructed as a platform for appearances: like a modernist home that doesn’t allow the traces of human activity in favor of maintaining the look of the architecture.

The work is connected by what a university should be and how we can fight neoliberalism. The thesis of this research considers the institution one of the few remaining liminal spaces for reimagining (and, in this case, “reimaging” — a useful typo that was kept in the installation) the world, a space outside of the realm of hegemonic thought to look at the world in new ways and develop new processes for it. It is a speculative, philosophical realm that, in design, presents new modes of operations to the world, or at least offers alternative ways of being through the integration of structures, objects, and modes of presentation; and art, which produces new ideas and shares them materially with the world, generates philosophical ideas in non-academic ways, and offers new ways of observing and interpreting the world.

To maintain this space there needs to be a continuous criticality running through the way that these institutions operate, the development of alternative pedagogies, and the ability to protect these practices through a protective coding during periods where the academic structures are under pressure from standardizing/neoliberal influences. In an unstable, uncaring, global environment where the idea of self-organization — let alone the survival of independent creative practices — has become economically unfathomable, the academic institution must be the place that provides protection for speculative practices that provide strains of radical alternatives to the system that we have today. (“Self-Organization!”, respond the elites, starry-eyed, when you ask for formal legitimation; glowing with warm nolstalgia for the early 90s, when they used the limited free trial of neoliberal benefits to get where they are today so they can continue to talk about progressive-style concepts while telling us to play by the rules.) The system must be flexible for the students and their practices, and not the other way around, the bureaucracy must provide legitimacy to the practices of the students rather than subjugating the development of new knowledges in favor of some bureaucratic or technological “higher power”, the building needs to work for its users instead of becoming a re-enactment of architectural proposal visualizations with students merely decorating the building, and the individual must be respected above all by these systems.

1 FOUCAULT, MICHEL. THE BIRTH OF BIOPOLITICS, LECTURES AT THE COLLÈGE DE FRANCE 1978-79. ED. MICHEL SELLERT. TRANS. GRAHAM BURCHELL. NEW YORK. PICADOR, 2004.

2 JOHNSTON, DEBORAH AND SAAD-FILHO, ALFREDO. NEOLIBERALISM, A CRITICAL READER. LONDON. PLUTO PRESS, 2005.

3 SPENCER, DOUGLAS. THE ARCHITECTURE OF NEOLIBERALISM: HOW CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE BECAME AN INSTRUMENT OF CONTROL AND COMPLIANCE. LONDON. BLOOMSBURY, 2016.

4 IBID.

5 DE BRUYUNE, PAUL AND GIELEN, PASCAL. TEACHING ART IN THE NEOLIBERAL REALM: REALISM VERSUS CYNICISM. ANTENNAE. VALIZ, AMSTERDAM 1977.

(from: Alternative Stabilities, Mater Thesis 2020)

KMD ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEOLIBERAL AESTHETIC (concepts developed)

The Appeal to Efficiency

The most immediate concept derived from the research is the appeal to efficiency and the prioritization of technology over the individual. The idea that technology and the optimal functioning of the system (in this case, neoliberalism) is more important than respect for the individual, individual agency, interpersonal relationships. When humanistic education is (mis-)placed into a neoliberal structure — both of bureaucracy and architecture, it becomes destroyed because the core element of those studies rely on mutual trust and respect, concepts that are entirely irrelevant to the dominant system of ordering.

The concept of efficiency and pure functionality is seen as the ultimate goodness in the neoliberal ideology, so the building celebrates its sterile qualities. Because of this, it is not just that the building does not offer comfort, or even that it does not make room for comfort; but that comfort itself is not allowed; being seen as both a safety issue and an impediment to the efficient running of the building — simultaneously enforcing the idea that its inhabitants must be constantly active and productive.1

The “Smart Building” as an Outsourcing of Autonomy

The automation of the “smart building” outsources autonomy to building and the state. The designer of the building makes multiple assumptions about how people in this institutions should behave, and then creates ways that leave little room for individual uses — the doors open only through motion sensors (that don’t even work smoothly), the lights turn on for the user, and yet if anything needs adjustment one must turn to the state, which requires self-disclosure (“why are you using that room?” “do you have permission?” “what do you plan to do in there?”) For example, changing the temperature in a project room requires a request to be made to the company that owns the building, lightbulbs take a few professionals to change, and access to different rooms must be granted. Automated environments passively implement obedience. It is like the ultimate psychological manipulation where one is controlled under the guise of being assisted. “Let me make this easier for you” the building says, making assumptions and creating virtualities about your behavior.

The Theory of the Multiple Gazes

The theory of the multiple gazes was more fully developed in this project. The window structures within the building create vast fields of visibility; for instance, Øvre hall, designed to be the “creative commons” of the building, is a field that can be viewed by the authoritative gave of the state and the punitive gaze of the police (through the technological gaze of the security cameras), the disciplinary gaze of administration, the evaluative gaze of professors, the — in this context — competitive gaze of one’s peers, and the inquisitive gaze of the general public. The project rooms often have the overlap of fewer gazes: professors, other students, the wayward visitor, yet they are also vitrines for showcasing processes. The open-plan working quarters permit a bit more privacy yet are always open to spontaneous visits from students and faculty. All of these have different types of panopticism but if one takes, for example, the project rooms with large glass windows: they are a space that puts the processes of art and design on display and generates a sort of performativity to the actions. This then enhances disciplinary functioning in many senses: self-regulation in front of others, obedience to the rules, and the articulation of formalizing movements of the disciplines (for instance, a painter would be pushed to act more like a painter, wielding a brush and stepping back to look at the work occasionally, a designer more likely to mimic the actions of a designer in a studio, using sticky notes on walls, drawing large mind maps, and sitting at a laptop, a video artist would take on the actions of a cinematographer, etc.)

The Window Structures of the Building

The concept of transparency2 is articulated both through the bureaucratic attitude (it is not enough to be honest, the student must be forthcoming, anything less is lying. The student must be self-disclosing to administration and faculty, yet most of the functioning is entirely opaque) and the structures of the building: students are constantly seen, professors often have temporary refuge in (sometimes shared) offices and yet the third floor is entirely opaque and unaccessible to students. In terms of visibility, the student is always open and exposed, (personal constructions for privacy are seen as a safety hazard) flexible, and available. While at the same time, an unweildly bureaucracy finds it too difficult to adjust to newly emerging creative practices, choosing instead to make administrative decisions in academic situations.

The Hub Space

Nomadism is often seen as a way of evading the hegemonic order, but with the introduction of the hub space in neoliberal architecture, the concept of nomadism becomes integrated into neoliberal strategies. It offers small sections of “smooth” spaces for individuals to navigate, at the same time refusing to provide any symbolism that the subject could critically analyze, giving away cognitive agency to their environment. At the end of The Smooth and the Striated, Deleuze warns: “Never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us” (Additionally, in Nomadology and the War Machine, it is described how nomadic tactics are often used by the dominant forces as well.)

The Commons as Synthetic Equalizer

This leads to the idea that the commons created a field of synthetic equality, that can harness the energies of subjects that are not treated equality within the system — as neoliberalism runs on the dynamic of inequality — to use towards the progress of the very system that subjugates them3. That by creating architectural spaces of the neoliberal version of openness, transparency, and freedom, the energies that are generated in those spaces become productive towards neoliberalism.

1 ALSO PRESENT IN FOUCAULT, MICHEL, DISCIPLINE AND PUNISH: “THE DISCIPLINE OF THE WORK-SHOP, WHILE REMAINING A WAY OF ENFORCING RESPECT FOR THE REGULATIONS AND AUTHORITIES, OF PREVENTING THEFTS OR LOSSES, TENDS TO INCREASE APTITUDES, SPEEDS, OUTPUT AND THEREFORE PROFITS; IT STILL EXERTS A MORAL INFLUENCE OVER BEHAVIOUR, BUT MORE AND MORE IT TREATS ACTIONS IN TERMS OF THEIR RESULTS, INTRODUCES BODIES INTO A MACHINERY, FORCES INTO AN ECONOMY”P210

2 FOUCAULT, MICHEL. THE BIRTH OF BIOPOLITICS, LECTURES AT THE COLLÈGE DE FRANCE 1978-79. ED. MICHEL SELLERT. TRANS. GRAHAM BURCHELL. NEW YORK. PICADOR, 2004.

3 “BENTHAM’S PROJECT AROUSED SUCH GREAT INTEREST BECAUSE IT PROVIDED THE FORMULA, APPLICABLE IN A WIDE VARIETY OF DOMAINS, FOR A FORM OF “TRANSPARENCY”, A SUBJUGATION THROUGH A PROCESS OF “ILLUMINATION” FOUCAULT, MICHEL, “THE EYE OF POWER”

4 THIS CAN CONNECT TO A CONCEPT IN MOTEN AND HARNEY’S THE UNDERCOMMONS; THE IDEA THAT BY PRESENTING ONESELF AS A SUBJECT IN SOCIAL OR POLITICAL PARTICIPATION, ONE SUBJECTIFIES ONESELF WITHIN THE SYSTEM.

KMD ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEOLIBERAL AESTHETIC (academic research)

The thesis for the academic portion of the research uses Foucault’s definition of neoliberalism: as the constitution of the neoliberal subject through market logic. The way that it manifests as a mentality in Norway: through the application of the market mentality to the public sector, rather than overt privatization. And how it is then diffused as a mentality through its manifestation as “common knowledge” (through hewing to social norms and the redefinition of terms) and through the design of architecture. This definition includes the idea that Neoliberalism is a form of governmentality - a rationality of governance that conditions the conduct of subjects in a particular way, a series of political and economic processes that direct everything towards the support of the free market, an ideology presented as matter-of-fact.

Aside from promoting a free competition among markets, neoliberalism promises a freedom for its subjects. But the type of freedom that it promotes is mostly a freedom within itself: Neoliberalism wants “free”, mobile, flexible subjects that move within its circuits. Unlike nomadic movements, neoliberalism wants free-moving subjects that can be carried by it rather by their own free will, and it ensures that they do by presenting itself as common knowledge and producing self-regulating subjects that have internalized its rationality.

In Foucault’s Birth of Biopolitics1, he describes neoliberalism as requiring inequalities to operate. So it needs to continuously create and exacerbate inequalities in order to thrive. It creates need and then offers solutions for it. (It is important to note, that at the time of these lectures, neoliberalism was not hegemonic, so his analysis was only highlighting the emergent currents of the ideology.)

In this way, neoliberalism mobilizes everything to operate within its systems: standardizing everything to make sure that it can be used as data, that it can be measured by the metrics of neoliberalism, and that a utility is derived from every resource; and within neoliberalism, everything becomes a resource: even the spiritual. These resources then rely on inequalities that fuel neoliberal processes. Everything is made to be productive towards the progress of neoliberalism, and any sort of reforms are then talked about within its confines (including “progressive” reforms like the circular economy).

Since the subject also internalizes neoliberalism, they begin to view themselves as an enterprising individual, basing their value on neoliberal metrics, and placing their self-worth on their utility and productivity within the neoliberal hegemony. Their behavior is based on capitalizing on opportunities and marketing themselves, while making themselves more observable and measurable within the system.

In education, this means that the student is viewed (and conducts oneself) as a student-entrepreneur. One that is at school to acquire marketable skills and a portfolio of competencies so that they can better position themselves in the market. This is also combined with neoliberalism’s need to turn everything into data and to measure everything. For this there are ways of measuring the students capabilities within the system, not just “translating” everything into quantifiable activity — measured on how useful it is to the system — but also imposing a framework of measurable activities onto them. In this way, students are conditioned into neoliberal subjects and to cope with this, students — and society, in general — are offered therapy and self-help advice on how to continue to be useful subjects to neoliberalism and become the best entrepreneurs to the system. It allows them to raise their self-worth by raising their productivity and desirability to the system. Everything within this system needs to be measurable, so time, energy, and activities are organized into modules that are then used as frameworks to condition the subject. Neoliberalism operates on a large scale, so bureaucracy is designed for a large scale and administration is downsized — making fewer points of interpretation — and students become treated as data in the name of fairness. Fairness in neoliberalism, in order to be efficient, is non-qualitative, and views all subjects based on a few selected metrics — metrics that are useful to the system. It then uses these metrics to asses which students would be most useful to it, which ones would be more efficient and effective to process into the market, and which ones are most reverent to its rationality. In art and design education, this means attempting to — at best, try to find a way to quantify these practices — and at worst, trying to create quantifiable modes of practices for this field. So not just translating these practices into some sort of “rational” metrics, but actually changing the academic processes to generate quantifiable activities.

This research examines how this is implemented through a combination of bureaucratic processes that implement these activities, and the framework of the building, which conditions conduct through the same rationality.

Neoliberalism operates through appeal to efficiency. In academics, bureaucracy and the flattening of subjects into data create efficiency. Anything that goes against this order, is seen as going against progress. Following Foucault’s comments on neoliberalism, bureaucracy creates problems and then offers solutions — there is a sort of disorienting atmosphere that is created by unnecessary formalities, and then more rigid formalities are placed on the subject to “solve” the chaos.

In architecture it is implemented in many ways: through the efficient running of the building — the KMD building only needs people to activate it and maintain it. Many activities are curtailed in favor of keeping up the efficiency and safety of the building.

The entire building seems to be designed around anxiety emergencies: hallways must be cleared, there are glow-in-the-dark markers and signs with running stick figures along with escape arrows all over the building, soft furniture is not allowed in the studio spaces as a fire hazard, everything is locked with key card access.

Neoliberalism in the Norwegian context is very in line with the Foucauldian notion of neoliberalism. Here, the rationality is dispensed by the state. A critical reader on Neoliberalism2 discussed how welfare states tend to rely on social solidarity, which already means that migrants and people on the margins are excluded. This also means that the main way that this type of society shifts into neoliberalization is through the redefinition of terms. It would be difficult to change society’s traditions to other systems, but it is very effective to begin changing the meaning of certain themes by assimilating them into the market mentality that is already presented as common sense; this way, “freedom”, “security”, “fairness”, “transparency”, “equality”, “democracy”, take on entirely different meanings and catalyze subterranean cultural shifts towards neoliberalism. These shifts are often much more deeply rooted because they take place within the collective mentality and cannot be overtly identified.

This bureaucratic/academic structure connects to the structure of the building. The work examines two case studies from the book Architecture of Neoliberalism3: One that looks at Ravensbourne College, and one that examines the Pompidou Centre as neoliberal structures, and comparing them to the KMD building. It examined the idea of the hub space, a place that allows freedom and “nomadic” behavior, where people opportunistically find spaces to talk and negotiate spaces to operate in — also a place where anyone can be viewed at any time. It is the hallmark of the “progressive” corporate space: a space that says “this is a fun place to relax and work” — and here, there is no distinction between work and free time: breaks never really feel like breaks and the thought of work is constantly present during times of leisure. “A general feeling of constant productivity prevails at all times”, writes Douglas Spencer — in neoliberalism, even leisure is made productive. Google workspaces were mentioned as an inspiration for the KMD building, and so there are hub spaces that create this type of atmosphere throughout the building. Another characteristic of neoliberal architecture is visibility: both Ravensbourne College and KMD have a public and private axis, with the public axis creating a field of visibility for the public.

These theories are then connected in the examination of the window structures within the university. The windows to the outside world are above, to make room for “museum walls” but also utilizing windows as light sources, not as something that one gazes through. The interior windows, however, become vitrines for showcasing the artistic processes. This then enforces a performative aspect to the creative processes occurring in the building: everything is for everyone, everyone is transparent, there is nothing that is not done for someone else’s gaze. There are windows in the floors and ceilings, windows into every room, and large panels of glass as walls.

This is then developed into a theory of multiple gazes: In the building, the student operates under the gaze of the state and police (who are connected to the surveillance cameras on the second floor), the evaluative gaze of professors, and — in the context of the “student-entrepreneur” — the competitive gaze of other students. And with the concept of the private axis, in theory, they are also under the public gaze; Not just in the public axis of the building, but also in terms of the requirements that they have checked off and the data that their activities generate that then goes under the scrutiny of detached entities.

What does this make of the “creative commons” of the buildings? Connecting the second floor space designed to be the “commons” at the KMD building to the previous research on Torgallmenningen, the concept that is supposed to be the progressive solution towards multiplicities and equality is examined. How can we feign “equality” within a series of unequal power structures? When people’s subject-positions require different energies to make contributions to the commons, and then others have more prominent voices and more accessibility to legitimacy, when peoples’ capabilities have different values and impact, how can we pretend that the commons are a great equalizer? And when placed under multiple gazes and processed into the neoliberal mentality, the commons become an open space that not only removes any possibility of architectural critique, but also becomes a space where the subject relinquishes any self-direction or resistance to the free space of neoliberalism. This leaves the subject to territorialize the space in a neoliberal way — for instance, some design courses in Øvre Hall become a series of forced, quantifiable activities done in a neoliberal style under the guise of a progressive freedom and “creativity”, at times under the gaze of professors imbued with the idealism of the neoliberal rationality, uncritically producing objects that fit into the dominant social order — only different in style because that is all that can be retained within these frameworks — alternative ideologies become hollowed out through the formalities of the neoliberal framework and only what is useful to it is preserved and offered protection. Without addressing the dominant rationality, the commons become a way of sublimating any counterculture or alternative creations into more fuel for neoliberalism and more content for the people on top of the hierarchy. In this way, the commons is treated as an equalizing safe space for voices to be heard, but really only creates the illusion of a safe space that encourages people to open up and become vulnerable so that their energies can be exploited. A passive field for the blossoms of critique to bloom so that they can be harvested and distilled by neoliberalism.

What is meant to be a liminal space for developing new practices and solutions for the world, a safe space that protects individuals as they push themselves psychologically, mentally, emotionally, and even physically becomes an energy-harvesting device when the mentality of the hegemony is applied.

Instead of providing small spaces of time, physical space, and mental space where students can be vulnerable so that they can push their work for a brief second, be elevated/suspended into a theoretical realm, away from the dangers of this type of exploration in the corporeal world, the institution that asks students to be open and vulnerable without providing any protection from the violence of bureaucracy and neoliberalism then becomes a mechanism that renders the students docile and malleable for the social realm, it objectifies, subjectifies, and prepares the body, mind, and soul of the student for integration into the hegemonic order by making their energies productive for it.

Terms that are seemingly friendly become redefined: “Fairness”, for example: rather than being qualitative everything is the same, there is no discernment. This maintains hierarchical power structures while at the same time keeping people within disciplinary confines. This is not an equality that is based on respect for others, it is a redefinition that has punitive effects on anything that disobeys the framework — a positive way of keeping people in their place.

This “redefinition of terms” concept is also tied to the idea of appropriation, absorption, and co-optation of any counter-practice by neoliberalism. Apple computers made appearances in both the architecture book4 and the teaching art book5 . The architecture book talked about how Apple computers arose out of the counterculture of freedom, of the open road, and turned this freedom into a totalizing enterprise. The teaching art book discussed how standardization in education was aided by the adoption of Apple computers as the main operating system used in creative practices (especially design). The architecture book also uses the appropriation of the theories of Deleuze and Guattari and of Affect Theory by neoliberal architects to implement a neoliberal conception of freedom. These theories are used as conceptions of freedom that omit any possibility from critical thought; they are used to support the idea of open, parametric landscapes free of any type of symbolism that “unburden” the mind from any discussion or evaluation of the architecture and give themselves over to the flows of neoliberalism. In this way, hub spaces, open floorplans, repeating patterns, all create a space where the subject gives oneself entirely to the circuits of their environment.

In my analysis of the KMD building, I also examine the theme of the “smart building” as a space that gives a feeling that the little things are taken care of (things that are considered givens based on assumptions) and yet that one is completely overpowered by technology. In this case, it is as if technology is a higher power. At KMD, the doors open without your physical effort, but you need to ask permission from a motion sensor, the lights turn on for you but if they malfunction one is helpless without a technician, the temperature can be adjusted only with the help of the government organization that owns the building. The entire machine shuts down at midnight and you can only get out. Students are tracked every time they use their key card to access a room. This creates a sort of helplessness, a reliance on the higher power of neoliberal technology.

A complete domination of the technologies of the building that sociopathically makes assumptions about your needs, makes you completely dependent on it, and then makes you seem like a criminal if you color outside the lines with your routine. The public axis of the second floor have cameras that are maintained by the state.

So the subject of the building and bureaucratic structures needs to be always open, forthcoming, visible, transparent, flexible, empathetic; while the administrative quarters are opaque, the mechanisms of operation of the building are obscured and out of reach, the bureaucracy is rigid (for efficiency) and policies are unfeeling (for fairness). A severe imbalance of power is upheld through these structures that leave no room for non-quantifiable practices.

The entire building and system is constructed as a platform for appearances: like a modernist home that doesn’t allow the traces of human activity in favor of maintaining the look of the architecture.

The work is connected by what a university should be and how we can fight neoliberalism. The thesis of this research considers the institution one of the few remaining liminal spaces for reimagining (and, in this case, “reimaging” — a useful typo that was kept in the installation) the world, a space outside of the realm of hegemonic thought to look at the world in new ways and develop new processes for it. It is a speculative, philosophical realm that, in design, presents new modes of operations to the world, or at least offers alternative ways of being through the integration of structures, objects, and modes of presentation; and art, which produces new ideas and shares them materially with the world, generates philosophical ideas in non-academic ways, and offers new ways of observing and interpreting the world.

To maintain this space there needs to be a continuous criticality running through the way that these institutions operate, the development of alternative pedagogies, and the ability to protect these practices through a protective coding during periods where the academic structures are under pressure from standardizing/neoliberal influences. In an unstable, uncaring, global environment where the idea of self-organization — let alone the survival of independent creative practices — has become economically unfathomable, the academic institution must be the place that provides protection for speculative practices that provide strains of radical alternatives to the system that we have today. (“Self-Organization!”, respond the elites, starry-eyed, when you ask for formal legitimation; glowing with warm nolstalgia for the early 90s, when they used the limited free trial of neoliberal benefits to get where they are today so they can continue to talk about progressive-style concepts while telling us to play by the rules.) The system must be flexible for the students and their practices, and not the other way around, the bureaucracy must provide legitimacy to the practices of the students rather than subjugating the development of new knowledges in favor of some bureaucratic or technological “higher power”, the building needs to work for its users instead of becoming a re-enactment of architectural proposal visualizations with students merely decorating the building, and the individual must be respected above all by these systems.

1 FOUCAULT, MICHEL. THE BIRTH OF BIOPOLITICS, LECTURES AT THE COLLÈGE DE FRANCE 1978-79. ED. MICHEL SELLERT. TRANS. GRAHAM BURCHELL. NEW YORK. PICADOR, 2004.

2 JOHNSTON, DEBORAH AND SAAD-FILHO, ALFREDO. NEOLIBERALISM, A CRITICAL READER. LONDON. PLUTO PRESS, 2005.

3 SPENCER, DOUGLAS. THE ARCHITECTURE OF NEOLIBERALISM: HOW CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE BECAME AN INSTRUMENT OF CONTROL AND COMPLIANCE. LONDON. BLOOMSBURY, 2016.

4 IBID.

5 DE BRUYUNE, PAUL AND GIELEN, PASCAL. TEACHING ART IN THE NEOLIBERAL REALM: REALISM VERSUS CYNICISM. ANTENNAE. VALIZ, AMSTERDAM 1977.

KMD ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEOLIBERAL AESTHETIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone Books, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics, Lectures at the Collège de France 1978-79. ed. Michel Sellert. trans. Graham Burchell. New York. Picador, 2004.

Spencer, Douglas. The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance. London. Bloomsbury, 2016.

Johnston, Deborah and Saad-Filho, Alfredo. Neoliberalism, A Critical Reader. London. Pluto Press, 2005.

Buckley, Brad and Conmos, John. Rethinking the Contemporary Art School: The Artist, the PhD, and the Academy. The Press of the Nova ScotiaCollege of Art and Design. 2009.

Gielen, Pascal. Institutional Attitudes: Instituting Art in a Flat World. Amsterdam. Antennae. Valiz, 2013.

De Bruyune, Paul and Gielen, Pascal. Teaching Art in the Neoliberal Realm: Realism versus Cynicism. Amsterdam. Antennae. Valiz, 2012.

Moos, Lejf . “Neo-liberal Governance Leads Education and Educational Leadership Astray” Danish School of Education, Aarhus University. 2017.

Mydske, Per Kristen and Lie, Amund. “Neoliberal Reforms – State, Market and Society: The Norwegian Experience” University of Oslo, Department of Political Science.

McDonald, Matthew, Bridger, Alexander J., Wearing, Stephen and Ponting, Jess. Consumer spaces as Political Spaces: A Critical Review of Social, Environmental and Psychogeographical Research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2017.

This work was also presented in an artists talk at Joy Forum in December 2019, and in a lecture in the Mobile Kitchen Course (Sveinung Unneland, Eamon O’Kane, Ane Hjort Guttu) in January 2020 at the Fine Art Department at the Faculty of Fine Art, Music, and Design at the University of Bergen in Norway.

POINTS OF ACCESS TO ASSOCIATED DISCIPLINES:

Excerpts from process document, academic descriptions, connections to other disciplines, reflexive text:

Project Overview

This transdisciplinary installation utilizes an ambient form of institutional critique combined with a scenography developed from spatial research on the university building to interrogate the creeps of neoliberal ideology within these structures: connecting the bureaucratic and administrative structure to the physical architectural structure of the building.

This project started from two different trajectories: I had decided to do a counter-surveillance of the institution in my first semester here, and then I became interested in the bureaucracy and maintenance codes that rule the school and overrode the creation of knowledges, artistic practices, and design processes through some of my expeirences. I had developed some concepts that I noticed during my interactions with the building and culture of the institution, and began exploring them through more focused spatial research and academic texts. I was also interested in the constitution of the subject in this context. The idea that a particular type of student was constituted within this type of environment.

I studied these two trajectories in both an academic process, and an artistic spatial research process which eventually intertwined into a cohesive research structure.

Art

The books are scanned, which is a type of photography. It creates a wallpaper— one of the examples that I use to differentiate between design and art (and their effects) is the idea that a wallpaper might be designed and then put into many homes, but it is not really meant to be looked at contemplatively — it is merely decorative, or maybe even functional in its effects.

In this case, we have a wall of photography, and it is all text. So in a way, it becomes a wallpaper with a contemplative, artistic function. Viewers are meant to look at the wallpaper contemplatively, and the wallpaper both carries information and has artistic value.

The installation also created a semi-dystopic environment that conveyed a feeling that the building generated: a cold and moody building that doesn’t need people, that signals to the higher power of technology and presents its neoliberal goodness by being as function-oriented and ultra-utilitarian as possible, its rejection of anything related to comfort and ultimate commitment to efficiency proves its reverence to the neoliberal order. It uses film and photography — for example footage of an automatic window slowly opening — to show a sort of melancholy detachment from the space, and combines this type of imagery with images of the overpowering technological workshops and exposed wiring.

Design

The texts created a format for the spatialization and presentation of philosophical/theoretical thought: it is unresolved, nebulous, abstract. It mocks and fetishizes the academic process: using multiple texts as authorities, being reverent to footnotes and notations. It also creates a more ethical presentation of fragmentary information. There have been trends in design to pull quotations for the use of graphics or posters that inevitably pull out most of the contextualization, leaving the quote vulnerable to mis-interpretation, re-interpretation, or re-appropriation. In this format, there are points of entry into the work through the use of pull quotes, but the passages are not pulled out of their context: they are surrounded by the original text, they are contextualized within the book and even the visible page number, and then of course there are footnotes. This allows for a fluid interplay of texts, without the distortion of their original intention. The spatialization also allows for a sort of analog multi-information channel that allows you to enter multiple conversations at once, connects the information thematically, but also allows the viewer/reader to enter the texts at any point, and navigate in any direction that they like, and still get an idea of the message — allowing there to be multiple accounts of the work. There are also echoes that refer to and connect each section within the work so it is a truly three-dimensional and dynamic reading experience. The images produce a scenography that appeals to sensory knowledge, not only showcasing the data that was collecting, but also informing the texts by conveying the mood of the space through multiple elements, subtly mimicking the outwards-facing structure of the building but in soft wood rather than shiny alumimum.

Exhibition Design

The installation was a hybrid of the informational exhibition that displays informational artifacts and research data, and an art installation that generates an experience for a viewer. The work uses spatial design to generate fragmentary theoretical configurations of texts and a scenography developed from spatial artistic research to transform the space. Angled pedestals served as information panels for (somewhat literal) “foot”notes, research images of the interior covered in plexiglass were presented as neoliberal icons, scenographic images were framed in extended frames to mimick the patterning of KMD’s architectural envelope.

Architectural Research

The architectural research viewed aesthetics as functional, not only in the sense that they convey an ideology, but that they generate an atmosphere that enforces and conditions a neoliberal subject. It transformed the phenomenological process by combining it with the analysis of power structures, and added a critical dimension to theories of affect.

It outlined what the neoliberal aesthetic is: not necessarily a unified look, but tendencies that indicate a particular code of conduct within the building. I then examine this architecturally-generated governmentality in relation to the types of artistic practices and design processes that it conditions — structurally, aesthetically, and conceptually.

Academic Research — Interplay of Texts:

The academic research borrowed performativity from the humanities: a few physical books were selected and marked up with tabs and sticky notes, pages were scanned, and key passages were highlighted. The different passages from the different texts validated each other, echoed shared themes, and supported my thesis (observations from my site-specific research, mean emails -- sent and drafts -- to the departments, themes based on my experiences). The main books that I used were: a book about teaching creative practices within a neoliberal hegemony (Teaching Art in the Neoliberal Realm), a book about neoliberalism in education and law (Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution) and a book about neoliberalism in architecturarl design (The Architecture of Neoliberalism).

I also supported the thesis with sections of sociological research papers, studies on spaces of consumerism, and papers from political science. This was also supported by other books about academics and also referred to Foucault’s lectures on Birth of Biopolitics. Since I am concerned with the constitution fo the subject within my researches, I selected sources that were also working with Foucault’s definition of neoliberalism (rather than Harvey’s or Lefebvre’s, for example) — mostly because the other definitions focus on the overt economic aspects of it and completely miss the main ways that these ideologies are entrenched. I have read Birth of Biopolitics about a year ago and had my own copy with me, so I was able to easily use a few key passages to support the references to it in the other books. In this way, it was interesting in the connections that were formed through these preoccupations and how quickly large bodies of work combined into something cohesive — at least as cohesive as one can get in the theoretical realm.

I began reading the Teaching Art book early last semester when I found it in the library after unintended clashes with bureaucracy at the school. I fell into it during the summer and received some sort of life-affirming energy from it, it reminded me why I love academics in the first place and brought me around more to the art mentality of the way the academy used to be run (my views about the academic process were somewhat different than my supervisor’s when I started, and parts of this book made me understand her perspective more and adjusted my view in a similar direction, also). Then I became interested in this topic of neoliberalism in the Norwegian context from my research on the commons last semester. I looked through many books in the different libraries and used the most relevant (and compelling) ones in the work. To connect the thesis to architecture and test some of my inclinations and conjectures, I had to request Douglas Spencer’s book from a different national library and became absolutely enthralled with it — and I was eventually in contact with the author which provided more insight to my research process.

Here, I was fetishizing the academic process. I had a conversation with a librarian at the humanities library where we lamented the replacement of physical books with digital copies in the library system. She reminded me that in the humanities, academics worked with multiple open books that they marked up and sourced in their work — she even mimed the activity as she was talking. I took on this performative action for my research and adopted the rationality of the legitimation of thought through other published texts. In the work, I used a similar material and processing for my own writing as I did for the scanned texts, enrobing my own, unpublished, writing in the legitimacy of the published texts.

The most exciting and rewarding part of the academic process — a process that I did entirely the way I wanted and received a maximum amount of pleasure from — was the interplay between the texts; by allowing a certain chemistry to occur between the readings, and not creating a predetermined framework or grid, and by spatializing the work, it created a sort of physical reading process, an analog processing of thought, by not aiming towards a traditional resolution or narrative, that made the thesis extremely true to to what it was. The meanings were not modified or contrived, there was a very “natural” and easy feeling about how the thesis materialized. Without any sort of wayfinding system, direct narrative, or didactic orientation, the installation created an ambient academic environment for contemplation.

view the process of developing the work here